Breakthrough in Organ Transplantation: First Human Kidney with "Universal" Blood Type Successfully Transplanted

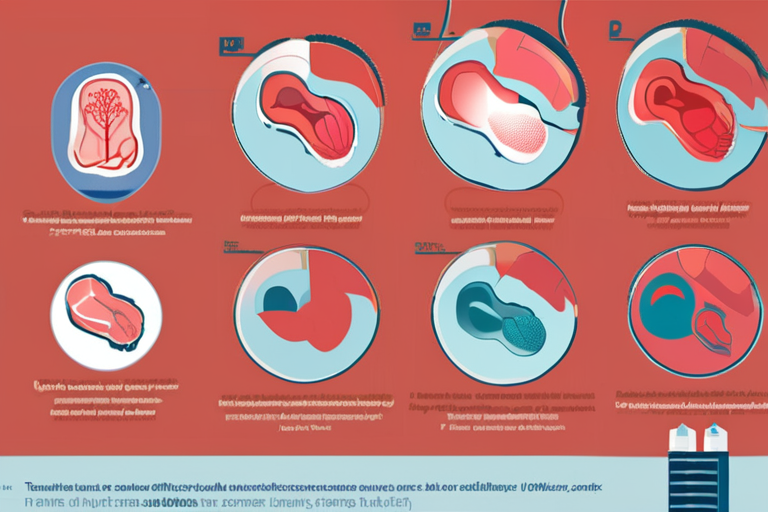

Vancouver, Canada - In a groundbreaking medical procedure, researchers from Canada and China have successfully transplanted a kidney modified to have the "universal" blood type into a 68-year-old brain-dead man. The achievement, which could revolutionize organ transplantation, was made possible by using an enzyme to convert the donor kidney's blood type from A to O.

According to Dr. Stephen Withers, a chemist at the University of British Columbia and lead author of the study, "We used an enzyme to remove the type-A antigens from the donor kidney, effectively converting it into a type-O organ." This modification allows the transplanted kidney to be compatible with recipients who have different blood types.

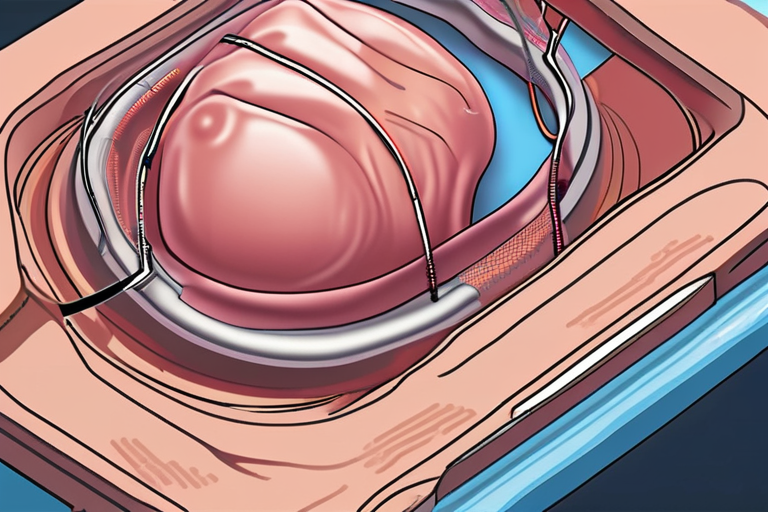

The procedure was performed in Chongqing, China, where the modified kidney was transplanted into the brain-dead man. Although the organ remained healthy for two days before showing signs of rejection, experts consider this a significant milestone in the field of transplantation medicine.

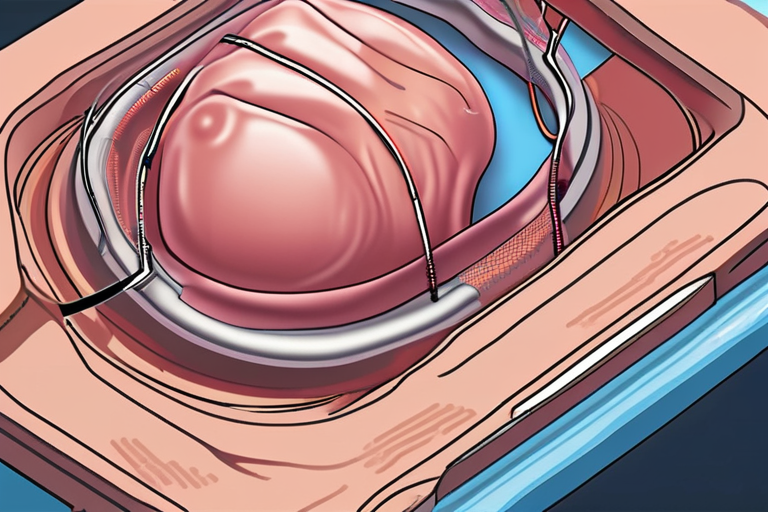

Currently, organ donation is limited by the need for matching blood types between donors and recipients. This can lead to long waiting lists and reduced access to life-saving transplants. The development of "universal" donor organs could alleviate these issues, making more people eligible for transplantation.

Dr. Withers explained that the enzyme used in this procedure is a type of glycosidase, which breaks down specific sugars on the surface of red blood cells. By removing the type-A antigens, the kidney's blood type is effectively changed to O, allowing it to be transplanted into recipients with different blood types.

While the success of this first human transplant is promising, experts caution that further research is needed to refine the procedure and improve outcomes. "This is an exciting development, but we must continue to study and optimize the process to ensure its safety and efficacy," said Dr. Withers.

The implications of this breakthrough are far-reaching, with potential applications in transplantation medicine and beyond. As researchers continue to explore the possibilities of "universal" donor organs, they may also shed light on new avenues for treating autoimmune diseases and improving organ compatibility.

In related news, scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have been working on a similar project using gene editing technology to modify kidney cells. Their research, published in the journal Nature, demonstrates the potential for gene editing to create "universal" donor organs.

The development of "universal" donor organs has significant implications for society, particularly in regions with limited access to transplantation services. As Dr. Withers noted, "This breakthrough could revolutionize organ transplantation and make it more accessible to people worldwide."

Additional Perspectives

Dr. Mark Davis, a transplant surgeon at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), commented on the significance of this achievement: "The ability to modify donor organs to be compatible with recipients is a game-changer for transplantation medicine. This could lead to increased access to life-saving transplants and improved outcomes for patients."

Dr. Davis also emphasized the importance of continued research in this area, stating, "While this first human transplant is a major milestone, we must continue to study and refine the procedure to ensure its safety and efficacy."

Current Status and Next Developments

The researchers involved in this project are now planning further studies to optimize the enzyme-based modification process and improve outcomes. They also aim to expand their research to other types of organs, including livers and hearts.

As for the patient who received the modified kidney, his condition remains stable, and medical teams continue to monitor him closely. The success of this first human transplant has sparked renewed hope for those awaiting transplantation and highlights the potential for innovative solutions in medicine.

Sources

Dr. Stephen Withers, University of British Columbia

Dr. Mark Davis, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)

Study published in Nature

*Reporting by Nature.*

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi

Hoppi