In the midst of World War II, a group of British scientists embarked on a series of daring experiments that would push the boundaries of human endurance and pave the way for one of the most pivotal moments in history: the Allied invasion of Normandy, known as D-Day. These scientists, driven by a sense of duty and curiosity, subjected themselves to extreme physical and mental stress, often with devastating consequences. Their bravery and sacrifice would ultimately contribute to the success of the mission, but at what cost?

Rachel Lance, a biomedical engineer and author of the book "Chamber Divers," delves into the fascinating and often disturbing story of these scientists in her latest work. Lance's research reveals the extent to which these individuals were willing to go in the name of scientific progress and national security.

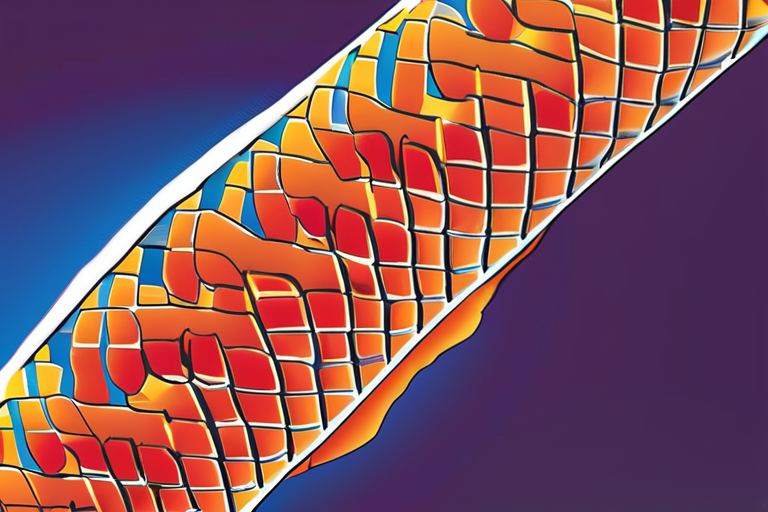

In the early 1940s, the British government was desperate to develop a new type of underwater breathing apparatus that would allow soldiers to survive the treacherous conditions of the English Channel. The device, known as the "Standard Equipment," was designed to provide a reliable source of oxygen for divers operating in the water. However, the technology was still in its infancy, and the scientists involved in the project were determined to test its limits.

To do so, they turned to a group of volunteers who were willing to undergo a series of grueling experiments. These individuals, often with no medical training or expertise, were subjected to extreme physical stress, including seizures, broken spines, and vomiting. The scientists, led by Dr. John Rawlins, a renowned physiologist, were determined to push the boundaries of human endurance and gather data on the effects of prolonged underwater exposure.

One of the most striking aspects of these experiments is the willingness of the scientists to put themselves in harm's way. Lance notes that many of the scientists involved in the project were "young, idealistic, and eager to contribute to the war effort." They were driven by a sense of patriotism and a desire to make a difference, often at the expense of their own well-being.

The experiments themselves were often brutal and inhumane. Divers were submerged in water for extended periods, sometimes for hours at a time, while scientists monitored their vital signs and recorded their experiences. The results were often catastrophic, with many of the divers experiencing seizures, broken spines, and vomiting. Some even lost consciousness or suffered from long-term brain damage.

Despite the risks, the scientists continued to push the boundaries of human endurance. They developed new technologies and techniques that would eventually lead to the creation of the Standard Equipment, a device that would revolutionize underwater operations and play a crucial role in the success of D-Day.

Lance's book sheds light on the human cost of these experiments and the sacrifices made by the scientists involved. "These individuals were not just scientists; they were also human beings with families, friends, and loved ones," she notes. "Their bravery and sacrifice should not be forgotten."

The implications of these experiments are far-reaching and thought-provoking. They raise important questions about the ethics of scientific research and the boundaries of human endurance. As Lance notes, "The line between scientific progress and human suffering is often blurred, and it's essential that we remember the sacrifices made by those who came before us."

Today, the legacy of these scientists and their experiments continues to shape our understanding of human physiology and the development of new technologies. As we look to the future, it's essential that we remember the lessons of the past and the sacrifices made by those who pushed the boundaries of human endurance in the name of scientific progress.

In the words of Dr. John Rawlins, the lead scientist on the project, "The price of progress is often paid in blood and sweat, but it's a price worth paying for the sake of humanity."

Share & Engage Share

Share this article