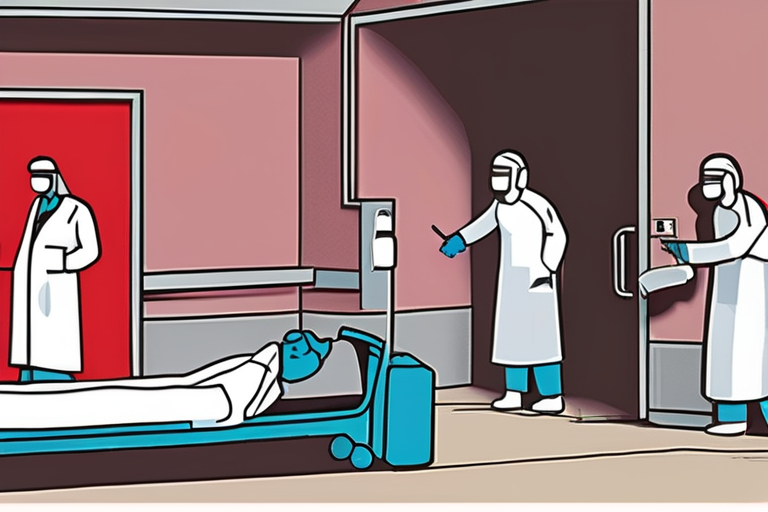

In the scorching heat of a West African summer, a young mother's life hung in the balance. She had made the perilous journey to a nearby clinic, only to find herself on the brink of death. The baby was delivered successfully, but the mother's bleeding wouldn't stop. The nurses at the clinic were powerless to stop the hemorrhage, and she was rushed to a bigger hospital across the river, where the blood loss had taken its toll. Her skin was pale, her organs on the verge of collapse.

This is a story that plays out every day in rural villages across the world, where access to medical care is scarce and the consequences of childbirth can be deadly. But it's also a testament to the resilience and resourcefulness of women like the mother in Gambia, who have learned to deliver babies with no supplies, relying on their own bodies and the wisdom of their grandmothers to save countless lives.

In many parts of the world, childbirth is a high-risk affair, particularly in rural areas where access to medical care is limited. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), every day, 830 women die from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth. In sub-Saharan Africa, the maternal mortality rate is a staggering 439 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared to just 14 deaths per 100,000 live births in developed countries.

But it's not just the lack of medical care that's the problem. In many cultures, childbirth is seen as a natural process, one that doesn't require the intervention of doctors or hospitals. In some African countries, for example, it's common for women to give birth at home, surrounded by family and friends. This approach may seem old-fashioned to some, but it's also a testament to the resourcefulness and determination of women who have learned to rely on themselves and their communities to deliver babies safely.

One such woman is Aisha, a midwife from a rural village in Mali. She has delivered hundreds of babies in her community, using traditional techniques and minimal equipment. "We don't need much," she says. "Just a clean space, some water, and a bit of cloth to tie the umbilical cord. The rest is up to the woman's body."

Aisha's approach is not unique. In many parts of the world, women are turning to traditional birth attendants (TBAs) like Aisha to deliver their babies. TBAs are trained in traditional techniques, but they also have a deep understanding of the cultural and social context of childbirth. They know how to read the signs of labor, how to prepare the mother and the baby for delivery, and how to handle complications when they arise.

But despite their expertise, TBAs often face significant challenges. In many countries, they are not recognized as legitimate healthcare providers, and they may not have access to the training or resources they need to do their job effectively. In some cases, they may even be seen as a threat to the medical establishment, which can be resistant to traditional approaches to childbirth.

One such TBA is Fatoumata, a woman from a rural village in Senegal. She has been delivering babies for over 20 years, using traditional techniques and minimal equipment. But despite her experience and expertise, she has faced significant challenges in her community. "The doctors and nurses don't trust us," she says. "They think we're not qualified to deliver babies. But we know what we're doing. We've been doing it for generations."

Fatoumata's story is a testament to the resilience and determination of women like her, who have learned to deliver babies with no supplies, relying on their own bodies and the wisdom of their grandmothers to save countless lives. But it's also a reminder that there is still much work to be done to ensure that all women have access to safe and respectful childbirth.

As the world marks the International Day of the Midwife, it's time to recognize the critical role that TBAs like Aisha and Fatoumata play in delivering babies safely. It's time to acknowledge the expertise and experience of women like them, and to provide them with the training and resources they need to do their job effectively. And it's time to recognize that childbirth is not just a medical event, but a social and cultural one, one that requires a deep understanding of the context and traditions of the communities we serve.

Ultimately, the story of the mother in Gambia is a testament to the power of women and their communities to deliver babies safely, even in the face of adversity. It's a reminder that childbirth is not just a medical event, but a human one, one that requires compassion, empathy, and understanding. And it's a call to action, urging us to recognize the critical role that TBAs like Aisha and Fatoumata play in delivering babies safely, and to provide them with the support and resources they need to do their job effectively.

Share & Engage Share

Share this article